Mapping out collapse research

Understanding the ways societies end

This post is the first in a living literature review on societal collapse. You can find an indexed archive here.

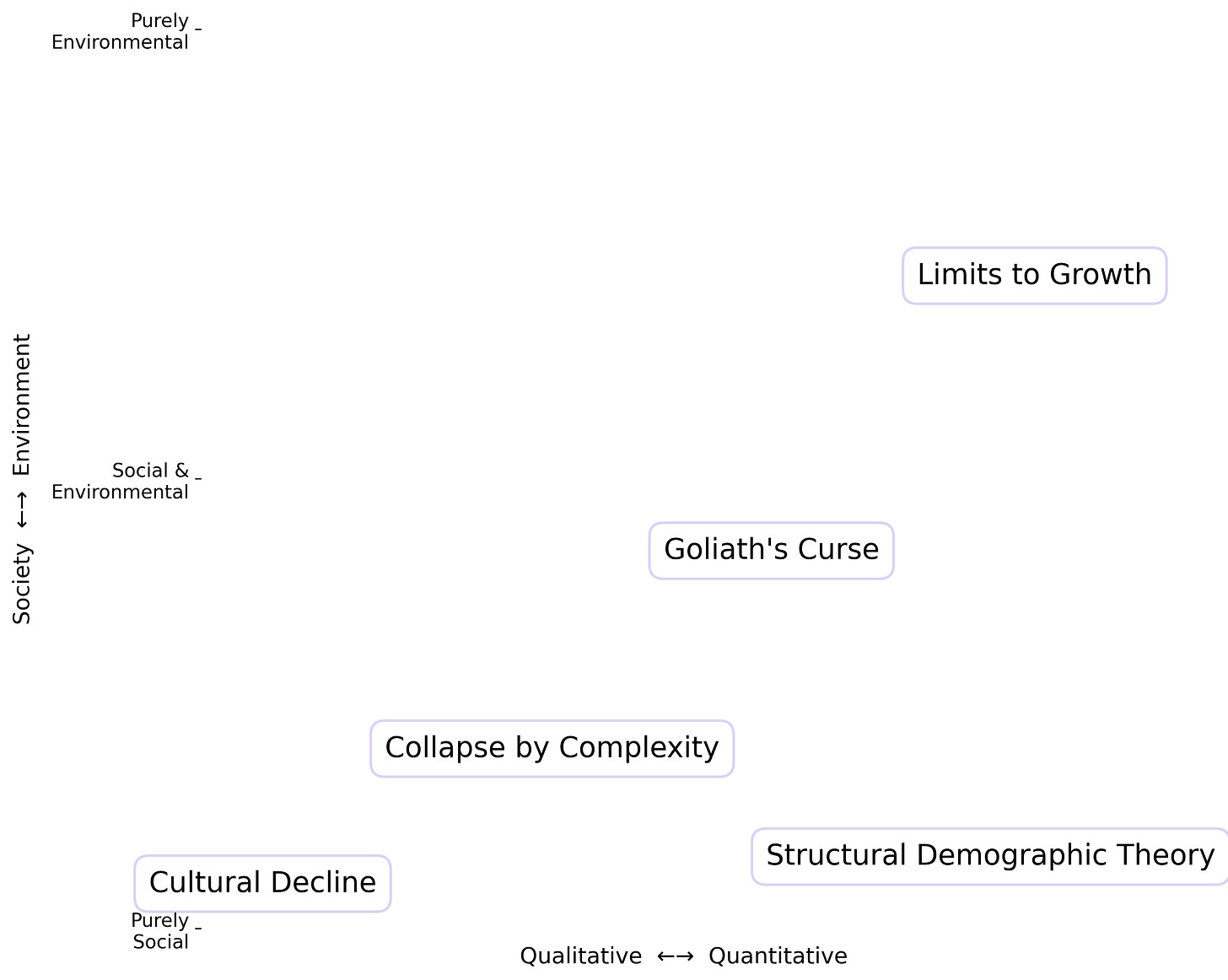

Societal collapse has been with humanity since the agricultural revolution, but only during the enlightenment did humans gain the means to understand these cataclysms in a systematic way. This line of research continues today, and in this post, I will map out how the field of collapse research has developed over time, what different schools exist (Figure 1) and what factors they emphasize as leading to collapse. Much of this is based on Brozović (2023), who read and summarized an impressive amount of collapse research. We will first explore the different schools of collapse research in roughly chronological order. These schools can also be seen as representatives of how we should think about collapse in general. After introducing these major schools, we’ll use them as a lens to begin investigating two important questions: what even is a collapse? And what causes it?

Figure 1: Schools of collapse research.

Traditional theories of cultural evolution

“Cultures rise through toughness and fall through their decadence”

In this school of research, cultures are seen as organisms. They develop and adapt, and if they fail to do so, they die. Much of it is originally based on the main work by Edward Gibbon, “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire”. In this opus, Gibbons explores what might have caused the end of the Roman Empire. According to him the main reason the Roman Empire (and thus possibly other cultures as well) ceased to exist was the loss of civic virtues in its citizens, caused by decadence.

His ideas were very influential for collapse research, and how collapse is viewed in general. For example, in 1926, Spengler’s “Decline of the West” argued “The West” peaked before World War I, and would subsequently crumble, because it had lost its ancient ways. However, today, this view on collapse is seen as discredited, as it is too simplistic, and often inscribes certain cultures as inherently more valuable than others. Still, these ideas are deeply ingrained, especially in western, conservative circles. There they are used for example to frame migrants as disruptors of culture, who will bring on the fall of civilization by corrupting enlightenment values.

Limits to growth

“People will always try to consume all available resources”

Limits to growth is the idea that the Earth has a fixed carrying capacity it can support in the long term. This kind of thinking has experienced several transformations over time. The first variant of this view is the concept of the Malthusian Trap, which was first developed by Thomas Malthus in 1798. The main idea of the Malthusian trap is that poor people will always have as many children as can be supported by society’s resources, so that available resources act as a strict regulator of overall population size, possibly via famines and other catastrophes (see an earlier post here for a more detailed explanation). This idea had a resurgence in the 1960s in the USA around the book “Population Bomb” by Paul Ehrlich, but quickly decreasing population growth in the 20th century has proven it untrue for post-industrial civilizations.

The idea of the Malthusian trap lives on today in the ideas of limits to growth by the Club of Rome (Meadows et al., 1974), in the notion of so-called planetary boundaries (Rockström et al., 2009) and the degrowth movement. Planetary boundaries are defined as parts of the Earth system that have to stay within certain boundaries to make this planet habitable for the long term. The underlying assumption is that human civilization developed in a stable window of environmental conditions in the Holocene, and is therefore adapted to it. Every transgression of those conditions could lead to collapse, as humanity is not adapted to the environment outside of them.

How rigid those boundaries are, and how much they could contribute to a collapse is hotly debated. For example, Kareiva & Carranza (2018) argue that from all planetary boundaries only climate change has a clear path to a potential collapse, while Cernev (2022) explores scenarios where also other overstepped planetary boundaries could lead to an increased chance of a global collapse . Some argue that the path from exponential growth to collapse is typical for any kind of civilization, even extraterrestrial ones (see here for a deeper explanation.

Collapse by complexity

“Societies get ever more complex, but at some point complexity cannot be supported”

In the complexity view on collapse (introduced by Joseph Tainter, 1988), societies have to continuously solve problems (for example, how to provide more food for their citizens). These problems arise from a society’s interaction with its environment and internal dynamics. The key assumption is that every solution found increases the complexity of the society, and thus the energy it needs to sustain itself. The trouble is, usually societies can only increase in complexity. Past solutions have to be permanently maintained, while new problems need new and additional solutions. For example, consider a sewage system. This stops people from simply dropping their feces in the streets, but you cannot “solve” sewage. Instead you have a very complex sewage system that you most continuously monitor, repair and extend.

Tainter also argues that problems arise if the energy return of investment declines, by which he means that you have to continuously increase the amount of energy you invest to get new energy. This happens because societies start with the most easily accessible energy and once this source of energy is used up, the next sources of energy will necessarily be more complex to access. A society collapses at the point where it lacks the energy to sustain the complexity it has accumulated (Brozović, 2023).

This theory is seen as the most compact theory of collapse, as it can be used for every society without having to make adaptations (Brozović, 2023).

Structural demographic theory

“History is made of recurring patterns and we can measure them”

If traditional theories of cultural evolution are a narrative based style of collapse research, structural demographic theory is the opposite and tries to be as quantitative as possible. The main proponent of this kind of history, Peter Turchin, uses mathematical modeling that relies on extensive data collected from history to explore societal dynamics in the past. This has resulted in some very impressive datasets about history (Turchin et al., 2023), which can be used to test specific hypotheses. One of the main findings in this field of research are called secular cycles (Turchin & Nefedov, 2009).

Secular cycles describe a recurring pattern in history. It starts with a growing population that also has room to grow. The growth leads to more resources for everyone, which leads to an overall cooperative atmosphere. However, at some point, the room to grow shrinks, so that people can only get more resources if they take it from others. Population increases also depress real wages whilst also leading to an overproduction of elites relative to elite positions.This decreases trust and peace until it possibly triggers a redistributive event, which could be something like a civil war, which in turn decreases the population and the cycle starts anew.

While this approach of history creates very elegant theories, it has also been criticized as being too simplistic and having a too narrow focus on easily measurable variables (Maini, 2020). The proponents of this school counter that only a large sample history can give you reliable results. In a recent paper, Daniel Hoyer describes the failures of past schools of collapse and links them all to being too focussed on small, biased samples and case studies (Hoyer, 2022). Hoyer thinks that only a large, representative sample gives you a chance of getting general insights (1).

Goliath’s curse

“Dominance hierarchies doom societies”

Goliath’s curse is the most recent addition to major collapse theories (introduced by Luke Kemp in 2025). It draws inspiration from all of them. Similarly to Structural demographic theory, it is more focussed on the social aspects, but also discusses major shocks, especially in the form of global catastrophic risk today.

The general idea of Goliath’s curse is storable resources enable dominance hierarchies that create inequality, weakening societies until shocks trigger collapse. This is all based on a large body of evidence, which starts from the belief that humans favor egalitarian societies, but that societies easily end up in a spiral of dominance. This spiral is started by people gaining access to storable resources (like grain). Once those are available, they can be amassed and inherited. Quickly creating a power differential, which allows some to gain power. With this power often comes violence and coercion. People can only bear so much of it and they rebel if it gets too bad. This cycle has repeated countless times by now and if we are not careful, the global society of today might end up in the same way. So, better to reduce inequality now, before a global collapse makes everyone equally poor (2).

What even counts as collapse?

So far we’ve seen four main approaches to thinking about societal collapse. The cultural school puts the blame on the cultural decadence of a society. The limits to growth school emphasizes societies pushing beyond the environmental envelope that can sustain them. The complexity collapse school emphasizes the unsustainable increase in social complexity. And structural demographic schools emphasize a shift from positive sum growth to zero sum conflict once room to expand reaches its limits. However, are all of those approaches even talking about the same thing?

There is no definitive definition of collapse. This has become even more true as collapse research has shifted from being a part of history, to the more transdisciplinary kind of research it is today (Brozović, 2023). Over time, collapse research has become less qualitative, and more quantitative (going from Gibbon to Turchin).

Some examples of collapse definitions:

Collapse is the fragmentation or disarticulation of a particular political apparatus and transformation is a broad concept engulfing different sorts of societal changes (Faulseit, 2016)

Collapse is a rapid, uncontrolled, unexpected and ruinous decline of something that had been going well before (Bardi, 2020)

Collapse is a drastic decrease in human population size and/or political/economic/social complexity over a considerable area for an extended time (Diamond, 2011)

All those definitions have one thing in common: They are rather vague. What counts as a drastic decrease? What is a significant loss? How would we even measure sociopolitical complexity? When reading anything about collapse, we should always keep in mind the definition of collapse the author had in mind, because drawing conclusions depends on it. Interestingly, even though the possible definitions vary, the past collapse events references are the same. In a certain way it seems that you could answer the question “When can we classify an event as collapse?” with “I know it when I see it”. For example, there seems to be a very broad agreement that the end of the Roman Empire can be counted as a collapse, independent of the specific definition of collapse.

Others argue against the idea of collapse as a whole. Lawler (2010) argues that, for instance, the fall of the Maya was not really a collapse, but more of a transformation to a different kind of society. However, at least to me, this seems to be mostly a semantics game. Whenever someone argues that historical event X was not a collapse, but a transformation, they typically still acknowledge that the society at hand underwent significant changes and societal complexity was lost. The disagreement is not about the event, but if it was quick, big and permanent enough to count as collapse. This ultimately boils down to a value judgment about the preferred definition of collapse by the person who is making the claim. As the definition of collapse is so vague this cannot be really resolved until there is a widely accepted definition of collapse. In this series I’ll be using a variety of definitions, though focusing primarily on the kinds of events that people regard as bad.

There is also the idea that collapse does not necessarily have to be bad. This was especially championed by Kemp (2025). Collapse ceases to be a problem if you are not really connected to the state anyway and if the state you lived in was coercive in the first place. Historically, this was quite often the case, with many people’s lives improving after the state around them collapsed. They did not lose much, except freedom from taxes and the main people who had a bad time were the elites of the collapsing society. This does not mean that is always good for the average Joe. Especially, in today’s highly connected world, it would likely be devastating and deadly for many, but we should keep in mind that collapse also can have upsides if it ends an authoritarian regime.

Frameworks for causes of collapse

Whereas the definition of collapse remains vague, the search for causes of collapse has found somewhat more crisp results. We have come a long way from Edward Gibbon’s explanation that the Romans were simply not virtuous enough to avoid collapse. In general, there is now the view in collapse research that monocausal explanations are too simplistic (Brozović, 2023). Still, in the explanations of collapse we can see a distinction between research focussing on society’s interaction with the external environment and research focussing on the internal mechanisms of a society or even viewing collapse as a concept that applies to all complex systems and not only societies. In the following I will show three frameworks which highlight the differences between these research directions.

Environmental Framework (Example: Jared Diamond)

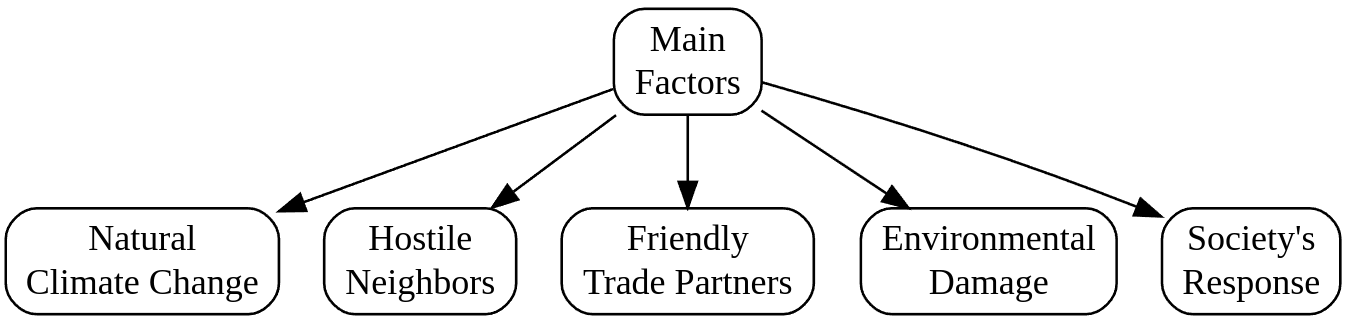

Let’s begin with Jared Diamond’s work, one of the most well known collapse frameworks, which focuses on society’s interaction with its environment. Overall there are five factors Diamond sees as the main drivers of collapse (though note Diamond believes it is possible to take actions to mitigate each of these factors - for example, a well managed societal response can help mitigate a sudden shift in the climate).

Figure 2: Jared Diamond’s main factors of collapse

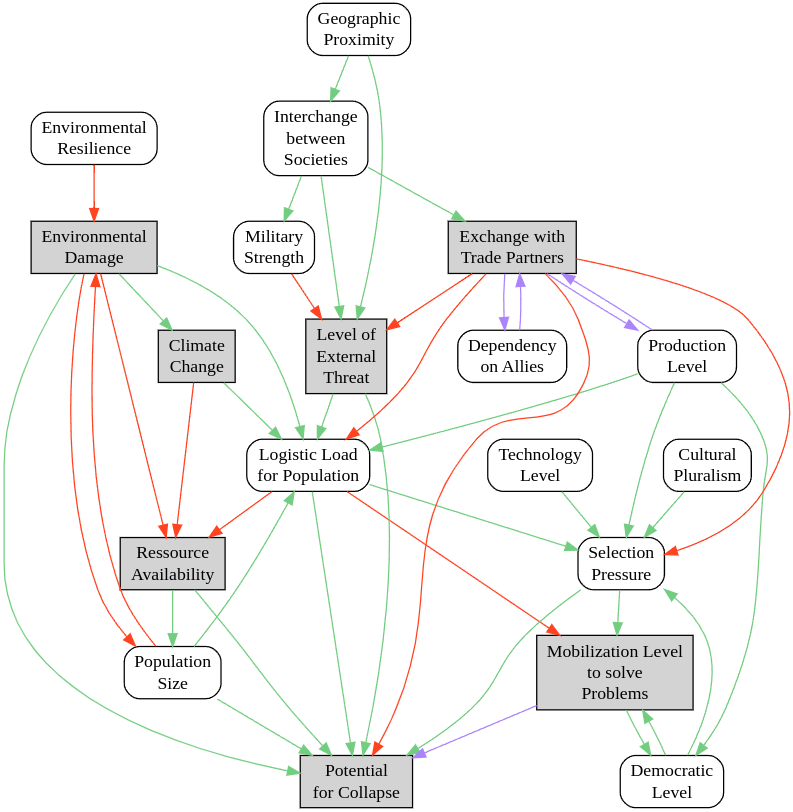

In addition to the five main factors, Diamond also identifies twelve environmental problems that are often connected to collapse. This framework has been used by others to create a conceptual model (Figure 3) (Carter, 2013). While no one has used it for further research yet, it highlights nicely the inherent complexity of trying to capture the essence of why collapse happens.

Figure 3: Reproduced figure from Carter (2013) based on Diamond (2011). Red: Negative Feedback, Green: Positive Feedback, Purple: Positive/Negative Feedback, Grey boxes: Main Factors, White Boxes: Subfactors.

While Diamond’s focus on the environment and humanity’s interaction with it makes intuitive sense to me, it should be noted that Diamond’s work has been criticized by anthropologists for being too focussed on the environment (e.g. Butzer (2012)), and misrepresenting or cherry picking historical evidence (Hunt & Lipo, 2012).

Societal Framework (Example: Karl Butzer)

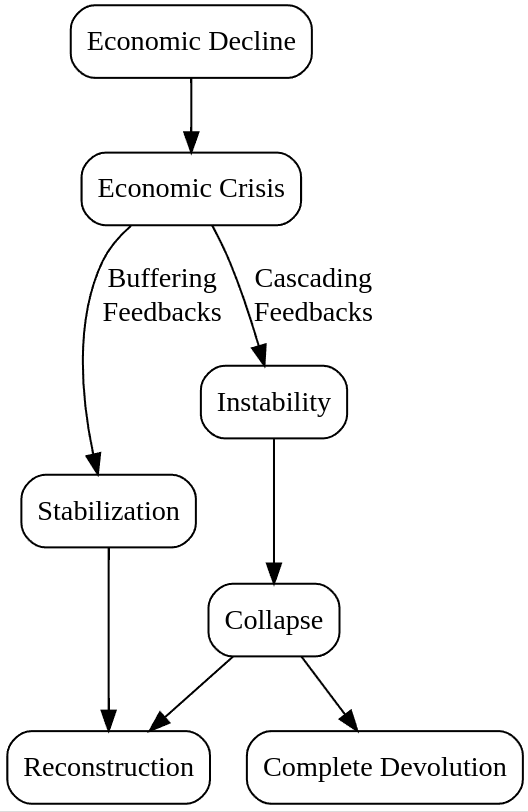

In contrast to Diamond, Karl Butzer focuses on the societal response instead of the environment (Butzer, 2012). The environment has a role in potentially triggering an economic crisis, but even this is only assumed to happen after an internally generated economic decline. When a crisis is triggered the reaction depends on whether society manages to end up in positive or negative feedback loops. In either case, reconstruction is possible, but is more likely to be incomplete after a collapse. Butzer further discriminates between a collapse and complete societal devolution, though he does not really define either. It reads as if you can still recover from a collapse, while a devolution leads to a complete dissolution of state-like structures. This focus on economic growth can also be found in other works, e.g. Samo Burja’s great founder theory (Burja, 2018).

Figure 4: Karl Butzer’s Framework of societal collapse.

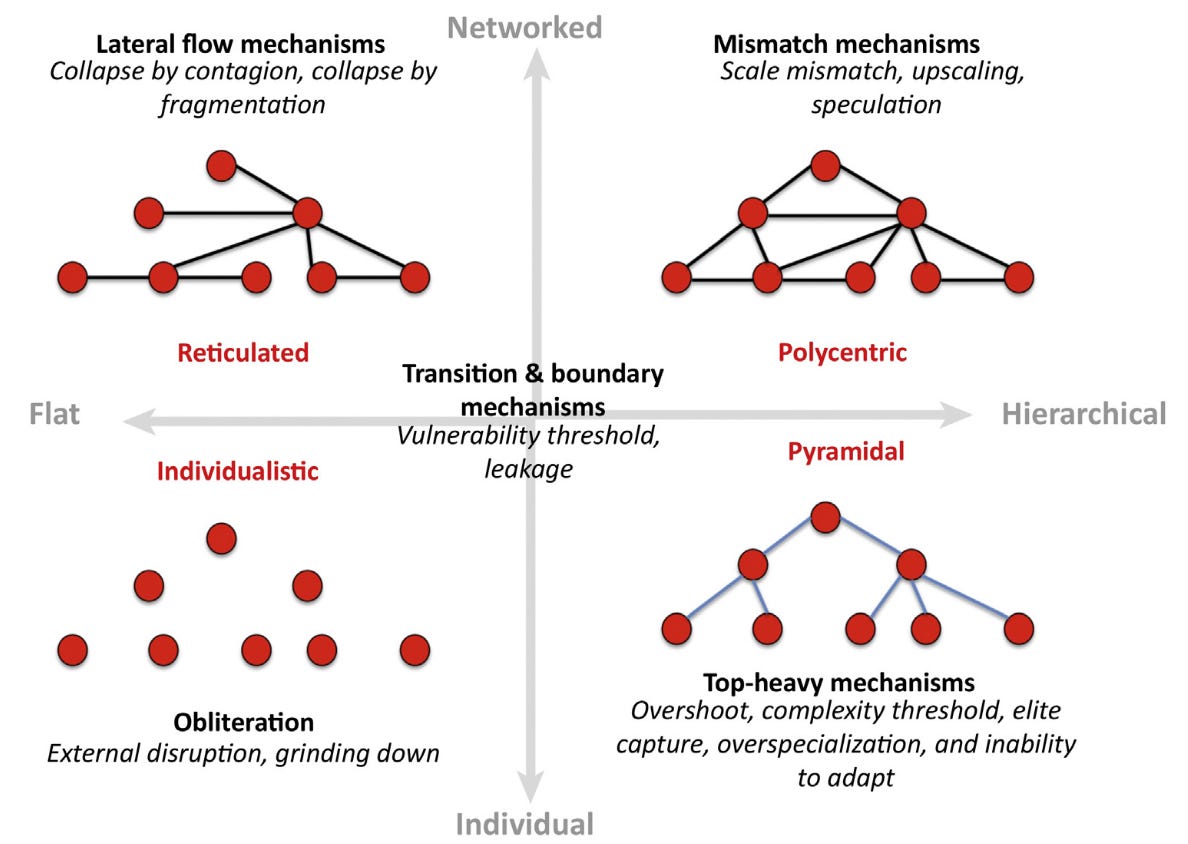

Meta Framework (Example: Cumming and Peterson)

The framework of Cumming & Peterson (2017) goes up one level in abstraction in comparison to the other two. While Butzer and Diamond are only interested in societal collapse, Cumming and Peterson see collapse as a more general phenomenon. The examples they look at are ranging from Bronze Age collapse to the collapse of bee hives. They come to the conclusion that the type of collapse that happens is based on the structure of the system. For example, if you have a hierarchical and individualistic structure you get the kind of collapse as Peter Turchin describes in his ideas of secular cycles. Overall, I find it more convincing, as it is a more holistic picture. It is also even more abstract than the other models proposed, which makes it more difficult to apply. However, Cumming and Peterson articulate that they see their work as the basis of an interdisciplinary study of collapse, which sounds quite promising.

Figure 5: Types of collapse based on the structure of the system from Cumming and Peterson (2017)

Synthesis

My main takeaway is that this field still has a long way to go. This is troubling, because in our society today we can see signs that could be interpreted as indications of a nearing collapse. There are voices warning that our global society has become decadent (writers like Ross Douthat), that we are pushing against environmental limits (for example, Extinction Rebellion), that we are having a decreasing return of investment for our energy system (for example, work by David Murphy) and that there has been an overproduction of elites in the last decades (writers like Noah Smith). This means we have warning signs that fit all major viewpoints on collapse. Moreover, new technological capabilities pose novel dangers that require us to extrapolate beyond the domain of historical experience. All this means that understanding how collapse really happens is rather urgent.

While the work of Jared Diamond and others brought the field forward by sparking a variety of discussions and new research, the field of collapse research is still in the process of finding a theory that is widely accepted in the community. There is no clear definition of what collapse is. Depending on their background, people argue for a bigger focus on the environment or a bigger focus on societal factors. This also seems to lead to a lot of discussion about semantics. Researchers criticize each other’s definition of collapse, even though most of the researchers seem to agree that there are clearly discontinuities in the historical record.

The closest to having an actual model of collapse prediction is the field of structural demographic theory. However, their focus is mostly on internal mechanisms of society, and less so on the interaction of society with the environment. A good way forward would be to couple structural demographic theory work with a more complex environmental model. This could also be combined with the work of Cumming and Peterson, to make it more widely applicable. However, this is a long term project, which requires much more work. Still, it would be an important piece of work, as we need to understand how past collapse has worked, to be safe against the complex, intricate and possible unexpected ways our society might be in danger today. Something along those lines has been proposed by Hoyer (2022) and partially implemented in Hoyer et al. (2024). I discuss this in another post in more detail, but the general gist is that it is difficult to attribute the survival of a society to a small number of factors. Still, if you had to choose the interplay of elite behavior, the state capacity and the size the external shock is probably a good place to start looking. This is obviously only a partial answer, but at least it starts from a solid empirical basisprovides a good place to start looking.

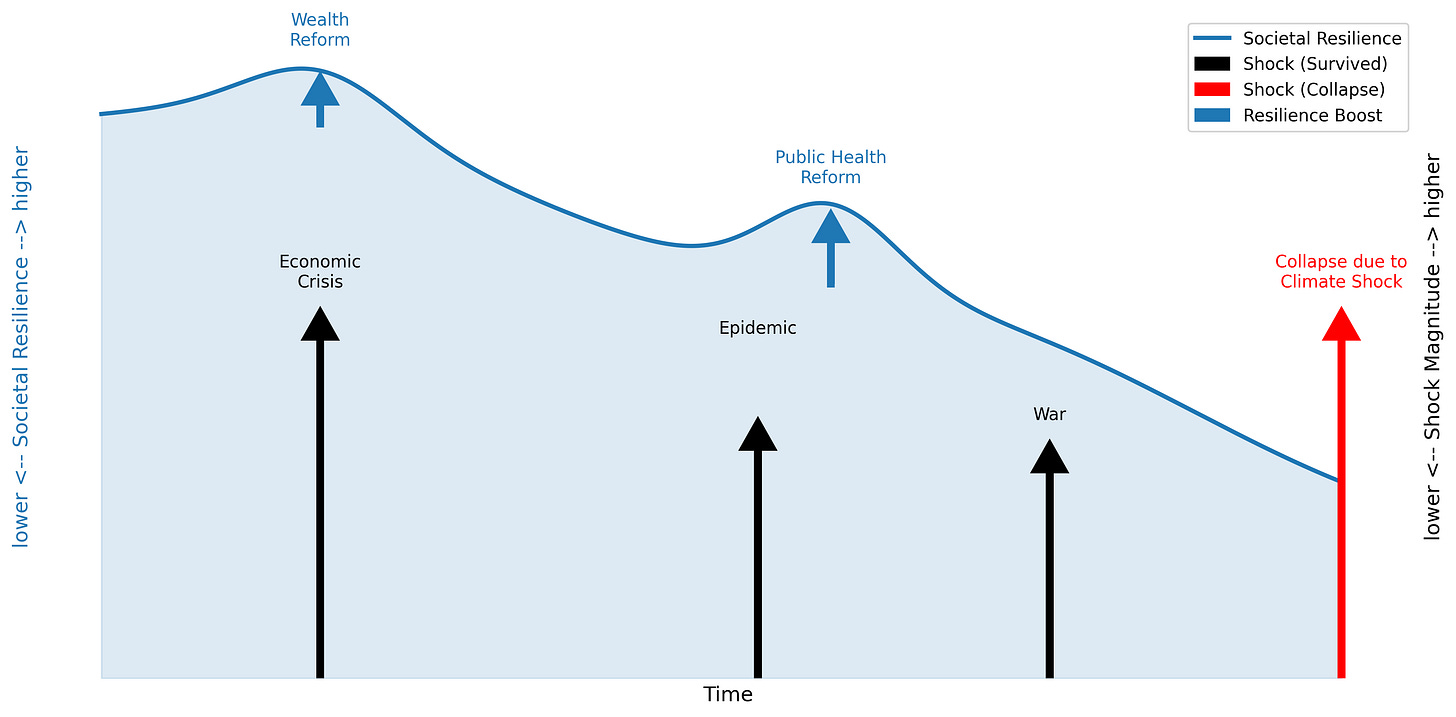

What also has become more clear to me while reading about all these different ways to think about collapse is that they all revolve how civilizations increase or decrease resilience and the likelihood and severity of external shocks they have to face. Obviously, all these theories focus on different answers to what causes these resilience changes and shocks, but also they are not really mutually exclusive. It seems more to me that they are focusing on facets of the same picture. And so if I had to lump them all together, I would say that collapse theories are about the forces that change resilience and how this resilience interacts with shocks. I tried to visualize this in Figure 6.

This is meant to show resilience shifts over time due to the decision a civilization makes. It can go up and down and every so often it gets hit by a shock of a certain size. If the shock is smaller than the resilience, the civilization moves on. If the shock is handled well, the resilience might even increase afterwards. But it can also lead to further deterioration. Finally, at some point the civilization is hit by a shock so large, it cannot be handled anymore and it collapses. I like this framing, as it is largely agnostic to what changes resilience and thus allows all kinds of theories being lumped together here. It also explains why very low resilience civilizations can survive for a long time. They just got lucky when it comes to the magnitude of shocks. Similarly, high resilience civilizations can still get toppled by a very high magnitude shock when they get unlucky.

These are just my two cents of how this all might fit together after reading a few hundred papers and a bunch of books around the topic. It is far from a finished theory, but maybe it inspires some of my readers to dig deeper.

Thanks for reading! If you want to talk about this post or societal collapse in general, I’d be happy to have a chat. Just send me a mail to existential_crunch at posteo.de and we can schedule something.

How to cite

Jehn, F. U. (2023, June 7). Mapping out collapse research. Existential Crunch. https://doi.org/10.59350/1r2zm-j9h84

Endnotes

(1) A longer discussion of structural demographic theory can be found here.

(2) A longer discussion of Goliath’s curse can be found here.

References

Bardi, U. (2020). Before the Collapse: A Guide to the Other Side of Growth. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29038-2

Brozović, D. (2023). Societal collapse: A literature review. Futures, 145, 103075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.103075

Butzer, K. W. (2012). Collapse, environment, and society. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(10), 3632–3639. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1114845109

Carter, M. J. (2013). A Sociological Model of Societal Collapse. Comparative Sociology, 12(2), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1163/15691330-12341262

Cernev, T. (2022). Global catastrophic risk and planetary boundaries: The relationship to global targets and disaster risk reduction. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-catastrophic-risk-and-planetary-boundaries-relationship-global-targets-and

Cumming, G. S., & Peterson, G. D. (2017). Unifying Research on Social–Ecological Resilience and Collapse. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32(9), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.06.014

Diamond, J. M. (2011). Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive. Penguin Books.

Faulseit, R. K. (2016). Beyond Collapse: Archaeological Perspectives on Resilience, Revitalization, and Transformation in Complex Societies. SIU Press.

Burja S. (2018, September 5). Great Founder Theory. https://samoburja.com/great-founder-theory/

Hoyer, D. (2022). Decline and Fall, Growth and Spread, or Resilience? Approaches to Studying How and Why Societies Change. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/43rgx

Hoyer, D., Holder, S., Bennett, J. S., François, P., Whitehouse, H., Covey, A., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Vustiuzhanin, V., Preiser-Kapeller, J., Bard, K., Levine, J., Reddish, J., Orlandi, G., Ainsworth, R., & Turchin, P. (2024). All Crises are Unhappy in their Own Way: The role of societal instability in shaping the past. OSF. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/rk4gd

Hunt, T., & Lipo, C. (2012). Ecological Catastrophe and Collapse: The Myth of “Ecocide” on Rapa Nui (Easter Island) (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 2042672). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2042672

Kareiva, P., & Carranza, V. (2018). Existential risk due to ecosystem collapse: Nature strikes back. Futures, 102, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.01.001

Kemp, L. (2025). Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse. Viking.

Lawler, A. (2010). Collapse? What Collapse? Societal Change Revisited. Science, 330(6006), 907–909. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.330.6006.907

Maini, A. (2020). On Historical Dynamics by P. Turchin. Biophysical Economics and Sustainability, 5(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41247-019-0063-x

Meadows, D. H., Club of Rome, & Potomac Associates (Eds.). (1974). The limits to growth: A report for the club of rome’s project on the predicament of mankind (2. ed). Universe books.

Rockström, J., Steffen, W., Noone, K., Persson, Å., Chapin, F. S. I., Lambin, E., Lenton, T., Scheffer, M., Folke, C., Schellnhuber, H. J., Nykvist, B., de Wit, C., Hughes, T., van der Leeuw, S., Rodhe, H., Sörlin, S., Snyder, P., Costanza, R., Svedin, U., … Foley, J. (2009). Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity. Ecology and Society, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03180-140232

Tainter, J. (1988). The Collapse of Complex Societies. Cambridge University Press.

Turchin, P., & Nefedov, S. A. (2009). Secular cycles. Princeton University Press.

Turchin, P., Whitehouse, H., Larson, J., Cioni, E., Reddish, J., Hoyer, D., Savage, P. E., Covey, R. A., Baines, J., Altaweel, M., Anderson, E., Bol, P., Brandl, E., Carballo, D. M., Feinman, G., Korotayev, A., Kradin, N., Levine, J. D., Nugent, S. E., … François, P. (2023). Explaining the rise of moralizing religions: A test of competing hypotheses using the Seshat Databank. Religion, Brain & Behavior, 13(2), 167–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/2153599X.2022.2065345

Well written, thanks!